Limited Landowner Liability

- Details

- Hits: 8032

Limited Landowner Liability on Recreation Lands

INTRODUCTION

Pennsylvania has a law that limits the legal liability of landowners who make their land available to the public for free recreation. The purpose of the law is to supplement the availability of publicly owned parks and forests by encouraging landowners to allow hikers, fishermen and other recreational users onto their properties. The Recreational Use of Land and Water Act (“RULWA”), found in Purdon’s Pennsylvania Statutes, title 68, sections 477-1 et seq., creates that incentive by limiting the traditional duty of care that landowners owe to entrants upon their land. So long as no entrance or use fee is charged, the Act provides that landowners owe no duty of care to keep their land safe for recreational users and have no duty to warn of dangerous conditions. Excepted out of this liability limitation are instances where landowners willfully or maliciously fail to guard or warn of dangerous conditions. That is, the law immunizes landowners only from claims of negligence. Every other state in the nation has similar legislation.

PEOPLE COVERED BY THE ACT

The “owners” of land protected by the Act include public and private fee title holders as well as lessees (hunt clubs, e.g.) and other persons or organizations “in control of the premises.” Holders of conservation easements and trail easements are protected under RULWA if they exercise sufficient control over the land to be subject to liability as a “possessor.” (See Stanton v. Lackawanna Energy Ltd. (Pa. Supreme Ct. 2005)(RULWA immunizes power company from negligence claim where bike rider collided with gate that company had erected within the 70-foot wide easement over mostly undeveloped land it held for power transmission)).

LAND COVERED BY THE ACT

Although on its face RULWA applies to all recreational “land”─ improved and unimproved, large and small, rural and urban ─ in the last 15 years or so, Pennsylvania courts have tended to read the Act narrowly, claiming that the legislature intended it to apply only to large land holdings for outdoor recreational use.

Courts weigh several factors to decide whether the land where the injury occurred has been so altered from its natural state that it is no longer “land” within the meaning of the Act. In order of importance:

(1) Extent of Improvements – The more developed the property the less likely it is to receive protection under RULWA, because recreational users may more reasonably expect it to be adequately monitored and maintained;

(2) Size of the Land – Larger properties are harder to maintain and so are more likely to receive recreational immunity;

(3) Location of the Land – The more rural the property the more likely it will receive protection under the Act, because it is more difficult and expensive for the owner to monitor and maintain;

(4) Openness – Open property is more likely to receive protection than enclosed property; and

(5) Use of the Land – Property is more likely to receive protection if the owner uses it exclusively for recreational, rather than business, purposes.

SITE IMPROVEMENTS

The following cases focus on the nature and extent of site improvements that might negate RULWA immunity:

● The state Supreme Court ruled that the Act was not intended to apply to swimming pools, whether indoor (Rivera v. Philadelphia Theological Seminary (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1986)) or outdoor (City of Philadelphia v. Duda (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1991)).

● RULWA immunity does not cover injuries sustained on basketball courts, which are “completely improved” recreational facilities (Walsh v. City of Philadelphia (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1991)).

● Playgrounds are too “developed” to qualify for immunity (DiMino v. Borough of Pottstown (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1991)).

● Playing fields generally are held not to be “land” within the protection of the Act (Brown v. Tunkhannock Twp. (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1995) (baseball field); Seifert v. Downingtown Area School District (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1992) (lacrosse field); Lewis v. Drexel University (Pa. Superior Ct. 2001, unreported) (football field); but see Wilkinson v. Conoy Twp. (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1996) (softball field is “land” under RULWA)).

● An unimproved grassy area at Penns Landing in Philadelphia was deemed outside the Act's scope, given that the site as a whole was highly developed (Mills v. Commonwealth (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1993); compare Lory v. City of Philadelphia (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1996) (swimming hole in “remote” wooded area of Philadelphia is covered by RULWA)). RULWA immunity has been found in several cases where people were injured at outdoor sites containing limited improvements:

● An earthen hiking trail in a state park is not an improvement vitiating the Act's immunity (Pomeren v. Commonwealth (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1988)).

● The owner of property containing a footpath created by continuous usage, which led down to the Swatara Creek, has no duty to erect a warning sign or fence between his property and the adjacent municipal park (Rightnour v. Borough of Middletown (Lancaster Cty. Ct. of Common Pleas 2001)).

● A landscaped park containing a picnic shelter is still “unimproved” land for RULWA purposes (Brezinski v. County of Allegheny (Pa. Commonwealth Ct. 1996)).

● An artificial lake is just as subject to RULWA protection as a natural lake, although the dam structure itself is not covered (Stone v. York Haven Power Co. (Pa. Supreme Ct. 2000)).

● An abandoned rail line in a wooded area is covered by RULWA, even where the plaintiff fell from a braced railroad trestle (Yanno v. Consolidated Rail Corp. (Pa. Superior Ct. 1999) (but may no longer be good law after Stone)).

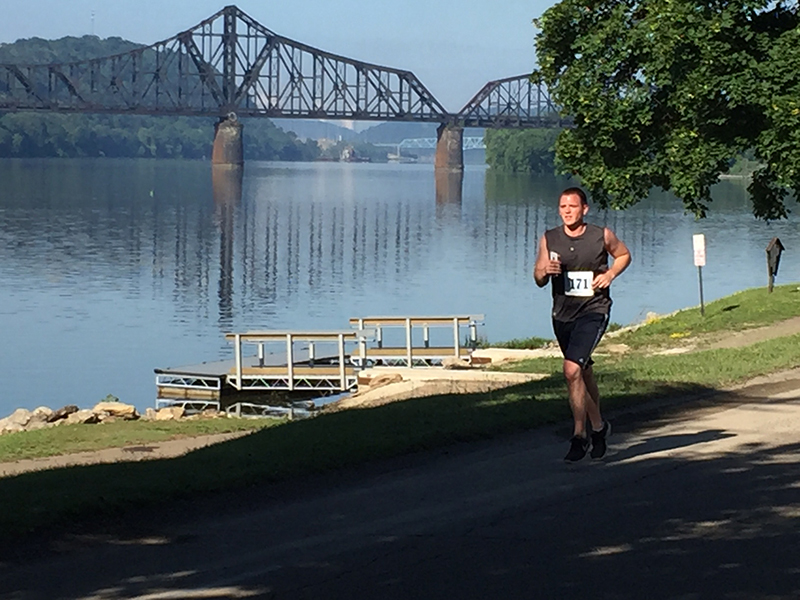

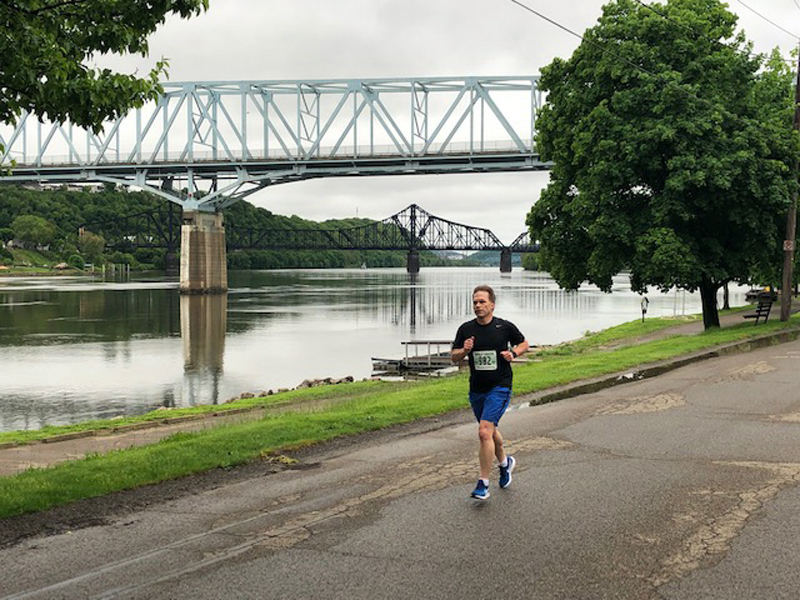

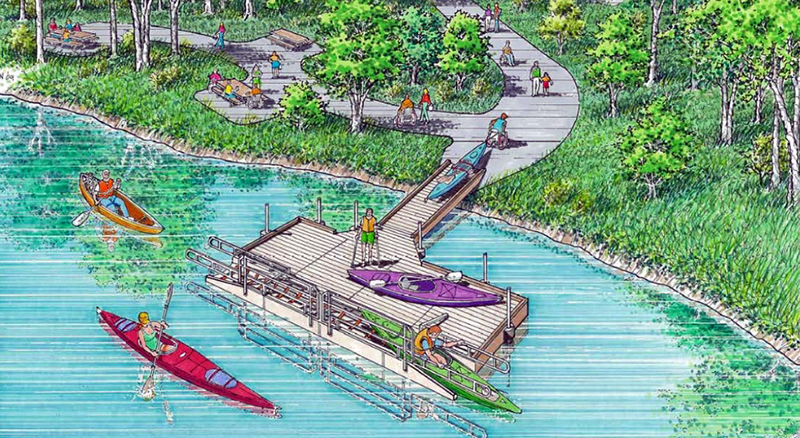

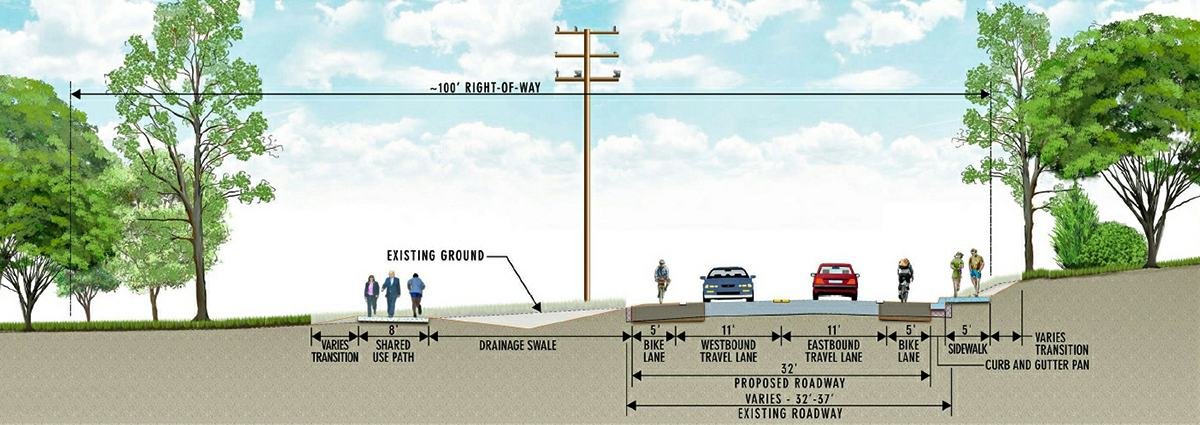

Uncertainty about what constitutes an improvement under the Act reportedly has had a dampening effect on efforts to improve public access to outdoor recreation sites. Public and private landowners are concerned that installation of fishing piers, boat docks, parking facilities, or paths and ramps for wheelchair use will strip much-needed RULWA immunity from otherwise protected land. A bill introduced in the state Senate in the late 1990s attempted to clarify that public access improvements would not affect immunity under the Act, but the legislation was not successful.

FAILURE TO WARN

As noted above, although negligence liability is negated by the Act, a landowner remains liable to recreational users for "willful or malicious failure to guard or warn" against a dangerous condition. To determine whether an owner's behavior was willful, courts will look at two things: whether the owner had actual knowledge of the threat (e.g., was there a prior accident in that same spot); and whether the danger would be obvious to an entrant upon the land. If the threat is obvious, recreational users are considered to be put on notice, which precludes liability on the part of the landowner. In a recent drowning case, for example, landowner Pennsylvania Power & Light Company claimed immunity under RULWA. The judge, however, sent to the jury the question of whether PP&L was willful in not posting warning signs. A previous tubing accident had occurred in the same location, and there was testimony that the dangerous rapid where the drowning occurred was not visible to people tubing upstream (Rivera v. Pennsylvania Power & Light Co. (Pa. Superior Ct. 2003)).

GOVERNMENTAL IMMUNITY

Interestingly, Pennsylvania's governmental immunity statutes, the Tort Claims and Sovereign Immunity Acts, shield municipalities and Commonwealth agencies from claims of willful misconduct. Liability only may be imposed upon these entities for their negligent acts. But, as noted above, where an injury occurs on “land” within the meaning of RULWA, the law shields landowners from negligence suits. In essence, public agencies are granted complete immunity for many recreational injuries. (See Lory v. City of Philadelphia (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1996) (city immune for both its negligent maintenance of recreational lands and its willful failure to guard or warn of hazards on that property)).

RECREATIONAL PURPOSE; PUBLIC ACCESS

Though not all recreational land is covered by the Act, the law's definition of "recreational purpose" is broad enough to include almost any reason for entering onto undeveloped land, from hiking to water sports to motor biking. (See Commonwealth of Pa. v. Auresto (Pa. Supreme Ct. 1986) (RULWA covers snowmobile injury)). This is true even if the landowner has not expressly invited or permitted the public to enter the property. However, where the land is open only to selected people rather than to the public in general, this will weigh against RULWA immunity. (See Burke v. Brace (Monroe Cty. Ct. of Common Pleas 2000) (lake located in a subdivision and open only to homeowner association members and guests is not covered by RULWA)).

NO USER FEE

Finally, charging recreational users a fee (which is different than accepting payment for an easement) takes the property out from under the Act's protection.

Source: Pennsylvania Land Trust Association